CS348b Final Project

Kurt Akeley, 6 June 2002

Motivation

The understanding of ray tracing that I am developing in

this course suggests that it breaks down into two fundamental operations:

- Ray Casting. Determining the intersection of a ray with the first

object in the scene that it meets. This involves acceleration structures,

intersection calculations, transformations, etc. And

- Ray Generation. Deciding, based on optics, statistics, probability,

sampling theory, surface characteristics, etc. what rays to generate. Some of

the calculations required to generate these rays are fairly deterministic

(e.g. reflection, refraction), some are regular even if not determined

specifically by the geometry (e.g. camera aperture), and some are completely

statistical in nature (e.g. diffuse and semi-specular surface parameters).

In general the calculations of Ray Casting (as defined above) are much

more deterministic and regular than those of Ray Generation, especially in the

case of scenes composed entirely of triangles or height fields. Given the rapid

increase in the performance of rendering hardware, and the trend toward

implementing special-purpose rendering hardware that supports ray tracing, it is

interesting to consider implementing algorithms that emphasize the deterministic

operation of Ray Casting, and deemphasize relatively complex forms of

statistical Ray Generation.

Goals

I identify two goals for this project:

- Height field Acceleration. Develop height field representations and

ray casting algorithms that are efficient and very high performance.

- Surface Simulation. Implement as a height field a microfacet-like

surface that can be shaded by simply casting and following reflected rays. (No

diffuse or semi-specular surface characteristics.) Attempt to match renderings

of this surface with those of the model microfacet-shaded surface.

Technical Challenges

Much of the challenge here falls in the domain of

computer engineering: minimizing data storage, identifying algorithm sequences

with early-out optimizations, making good use of hardware caches, and trading

off setup and execution time effectively. A lesser challenge is tuning a

high-resolution geometric surface to match the characteristics of a microfacet

shader.

Code Optimizations

For height field optimization:

- Optimized triangle intersection. Starting with the algorithm

described in "Fast, Minimum Storage Ray/Triangle Intersection", I implemented

intersection code that is optimized for a single cell in a height field. Such

a cell comprises two triangles that share an edge. This shared edge is used as

"edge2" in the algorithm, allowing much duplication in computation to be

avoided. Furthermore the intersection code's flow of control is organized as

an expanding tree, allowing computation for each triangle to be performed only

as needed. (But requiring some duplication of code to implement all the

paths.)

- Object coordinate intersection. The "walking" of the height field

almost has to be done in object coordinates, as is the bounding box test. The

triangle intersection code now also operates in object coordinates. No

precomputation is done, and only the provided height field values are stored,

so setup is very fast. Normals are computed only when an intersection is

detected.

- Fast above/below rejection. Even the accelerated quad intersection

test is expensive, so it makes sense to do trivial rejection of cells when

possible. When "MINMAX" is defined, the code compiles to a version that

computes entry and exit height values for the ray as it is traced. If the

ray's height is increasing, each cell first tests if the ray's entry height is

above the maximum for the cell, or the ray's exit height is below the minimum

for the cell. Alternately, if the ray's height is decreasing, each cell first

tests if the entry ray height is below the minimum for the cell, or the ray's

exit height is above the maximum for the cell. Separate code loops are

implemented for the increasing height and decreasing height cases, to minimize

the code length within the loops. Rather than storing a minimum and maximum

value for each cell, which would triple the storage requirement for the height

field, two 2-bit indexes are stored for each cell. (Thus the storage increase

is 25% for a single byte.) Since the height field is contiguous, the ray must

intersect a triangle to go from above to below the height field surface. So an

additional optimization could be made to reduce the min/max test to a single

test per cell. I have not done this, though.

- Tiled storage. Storing large arrays in the obvious 2D manner can

result in poor memory coherence when tracing a path. Tiling is a well-known

solution to this problem. When "TILED" is defined, the code compiles to a

version that does simple bit arithmetic on all cell X and Y addresses,

allowing 2D locality of data reference. I made no attempt to align these 2D

tiles with cache lines, however.

- Height field replication. I also modified the heightfield code and

the the API module to allow a single height field to be replicated in X and Y.

In RIB the replication factor for a dimension replaces the text string

"nonperiodic" in the PatchMesh primitive. Thus extremely large tiled fields

can be defined with the data of a single tile. The data size in a dimension

that is replicated must be a power of 2, however.

Performance

Performance of various code versions

|

Setup (sec) |

Intersect (sec) |

Total (sec) |

Code (lines) |

| Original |

35 |

1179 |

1213.9 |

75 |

| HW2 |

16 |

18 |

33.9 |

450 |

| Quad Test |

4 |

10 |

13.8 |

750 |

| Min/Max |

4 |

6 |

10.3 |

1175 |

| Tiled |

4 |

6 |

10.3 |

1200 |

Surface Model

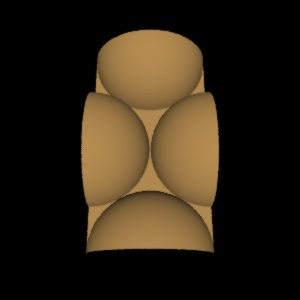

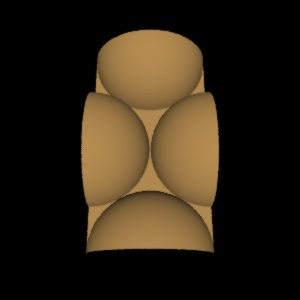

A simple C program

generates a height field that is a hexagonally packed array of hemispheres.

One tile of its output, represented as a 1024x1024 height field, looks like

this:

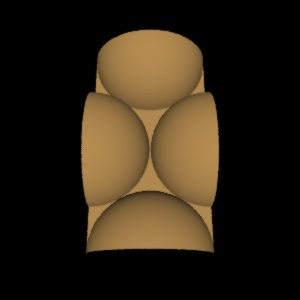

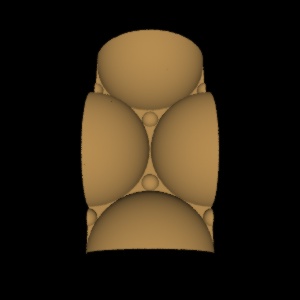

The hemispheres cover roughly 90% of the area in this tight packing. If

smaller hemispheres are inserted into the interstitial spaces, the coverage can

be increased to roughly 95%:

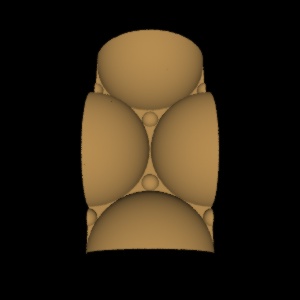

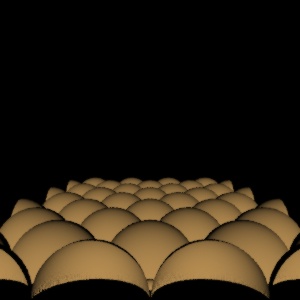

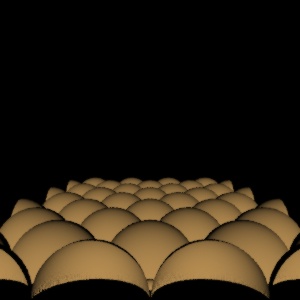

All the subsequent renderings were done using this interstitial packing,

though it likely has a very small effect on the results. Because unmodified

versions of LRT cannot handle height field replication, I ran the benchmark

tests using the following 1024x1024 height field. Note that the single height

field defines a 4-tile by 4-tile surface:

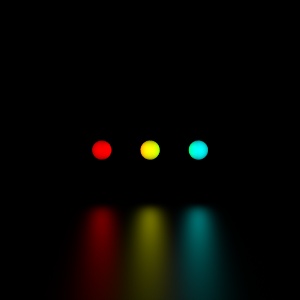

Images

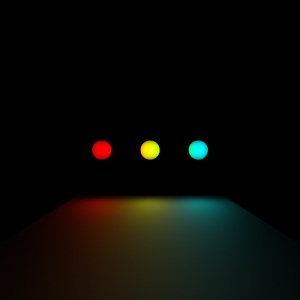

I rendered images of the reflection of three small colored

spheres of a near-horizontal planar surface. The "traditional" images use a

truly flat surface whose material parameter is set to

Surface "shinymetal" "Ka" 0 "Ks" .25 "Kr" 0 "roughness"

rough

where rough is varied. To make the lighting work

properly, I added point light sources at the centers of the spheres. It is these

light sources, rather than the spheres themselves, that actually are "reflected"

off the surface.

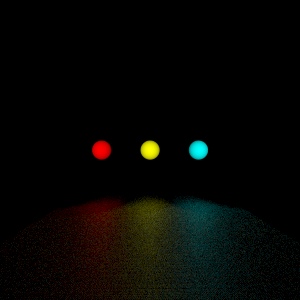

The microfacet renderings all replace the flat metalic surface with a

replicated height field based on the tile described above. The tile replication

is 256x256 in each image, resulting in over 100 billion triangles. The surface

material is specified as purely reflective

Surface "shinymetal" "Ka" 0 "Ks" 0 "Kr" 1

No lights

are included, so the images simply show the reflection of the small colored

spheres off the microfacet surface. To match variations in the roughness of the

traditional images, the microfacet surfaces are scaled vertically, resulting in

highly warped hemispheres.

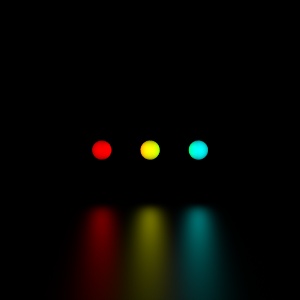

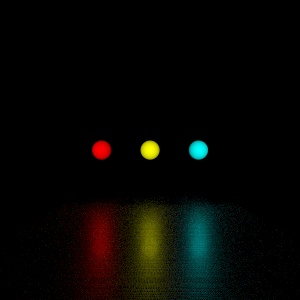

The first image comparison is at low roughness (high specularity) and is a

fairly good match:

| Traditional Rendering |

Microfacet Rendering |

| (Roughness = 0.01) |

(Vertical Scale = 0.1) |

| (4 Samples / Pixel) |

(256 Samples / Pixel) |

|

|

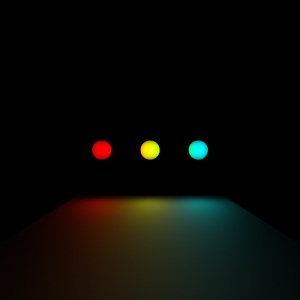

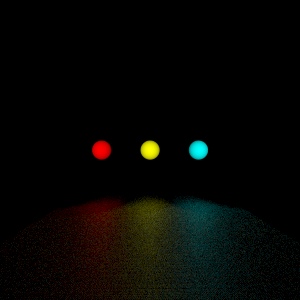

The second image comparison is at higher roughness, hence less sharp, and

here the match isn't as good. Note that even with 256 samples per pixel the

Microfacet rendering is undersampled in terms of shading.

| Traditional Rendering |

Microfacet Rendering |

| (Roughness = 0.1) |

(Vertical Scale = 0.3) |

| (4 Samples / Pixel) |

(256 Samples / Pixel) |

|

|

Conclusion

I am happy with the results of tuning and extending the

height field capability of LRT. The performance increase of optimized

intersection, reduced initialization and storage, and min/max testing are

significant, and came with reasonable code complexity. I was surprised that

tiling the memory access had no positive effect on performance, but I also

didn't investigate this very carefully. It is possible that careful alignment

with cache lines would make a difference.

The image matches are close enough to demonstrate the feasibility of modeling

surface reflectance as pure geometry, though there is certainly room for

improvement here. While it is instructive to see that a straightforward ray

tracer can handle huge surface complexity (100's of billions of triangles

served) it is more instructive to see just how much complexity is required to

brute force shading this way. At 256 samples per pixel the shading is just

adequate, compared to 4 samples (and it could be one) for the typical shading

approach. It sure pays to do this stuff right!

Thus, regarding the motivation of this project, I'm convinced that brute

force geometric rendering (emphasizing Ray Casting over Ray Generation), while

perhaps attractive in a simplistic hardware sense, is almost certainly a losing

proposition for even the simplest of scenes. Looks like statistics, probability,

and all the rest of the theory are here to stay.

LRT Code