Project Writeup : Sakura ("Cherry Blossom")

Team

- Tom Wang

- Priscilla Pham

Inspiration Images

|

|

|

|

Overview

- Sakura trees (also known as cherry blossom trees) are among the most beautiful trees in nature and also present a worthwhile rendering challenge. In addition, we will procedurally model blossom petals by using an adaptation of the rose curve. Finally, we intend to employ subsurface scattering on the petals to capture the realistic details of softness and faint translucency.

Tree Overview

- I model the tree procedurally with a modified L-system (defined with probability distribution functions along each depth of recursion) using generalized cylinders. I then generate a per-cylinder displacement map based on the geometry of the cylinder to add natural bark perturbation, enhancing realism. Next, I overlay with a per-cylinder bump map to emulate the circular indents present in lentical bark. Finally, I texture map a cherry blossom bark onto each cylinder. I provide technical details of each component below.

Procedural Tree Generation - Tom

L-system Background

- An L-system is a parallel string rewriting system, in which a simulation begins with an initial string called the axiom, which consists of modules, or symbols with associated numerical parameters. In each step of the simulation, rewriting rules—or productions—replace all modules in the predecessor string by successor modules. The resulting string can be visualized as a series of commands that link nodes, represent rotations, and distances between nodes.

Probability Distribution Function Implementation

- I model each part of the tree as generalized cylinders and control the look of the tree with the following parameters:

- Bottom radius

- Top radius

- Height

- 3D Rotation and Translation

- Initial radius fade (how much smaller the start radius of a sub-branch is)

- Final radius fade (how much smaller the end radius of a sub-branch is)

- Gnarling (overall displacement for next cylinder in link) Each cylinder is composed of a mesh of vertices in triangle strip format - these vertices are oriented as 'slices' (subdivisions around the main axis of the cylinder) and 'stacks' (subdivisions along the main axis of the cylinder). I am using a heavily modified gluCylinder() approach. Parameters are defined to be within certain ranges, depending on the level of branching, and are chosen with a uniform probability distribution function. For example, the trunk defines:

- Trunk radius - [1.7, 2.0]

Tree Rendering (Tom)

- In the context of procedural tree branch generation, an L-system can be defined as a series of generated cylinders of varying 3D orientation, thickness, and length. Since the L-system defines a particular grammar for branch generation, we will fine-tune the grammar and production rules of our 3D L-system to match the cherry blossom tree species. In addition, we will introduce probability models based on observations in nature (number of branches from a sakura tree, depth of branching) to match randomness in nature. With more time, we would like to enhance the branch models to be more advanced with general cylinders.

- We would like to emulate the biological properties of cherry blossom trees and will study real trees in nature to create a probability distribution function of branching possibilities (define angles in 3D as well as lengths) that best mimics real trees. This PDF will be defined as a normal distribution over a series of parameters varying by depth of branching (trunk is thicker and longer than a final leaf branch). Finally, the PDF will be species specific (a weeping willow, for example, has branches that point down, whereas a sakura tree demonstrates little if any negative Z-axis rotation).

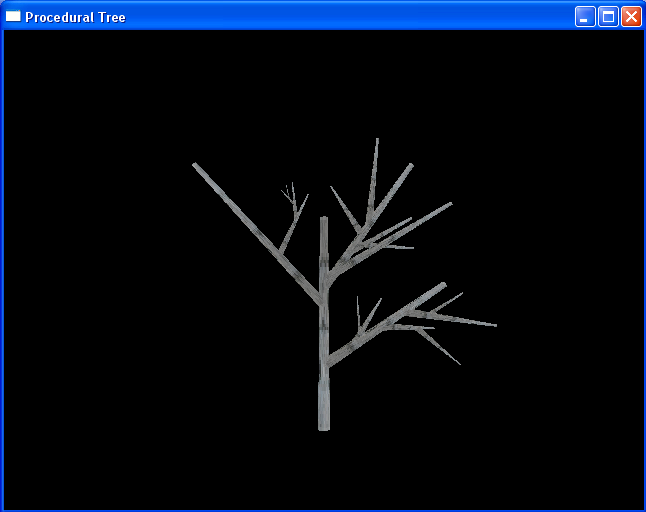

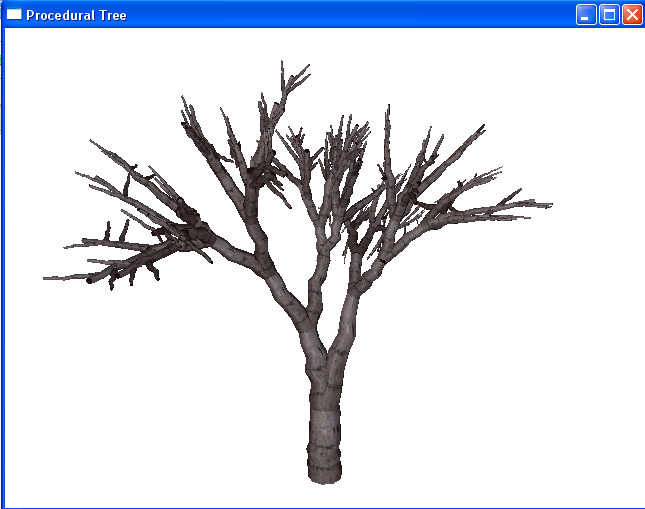

- An example of a simple implementation is the following image:

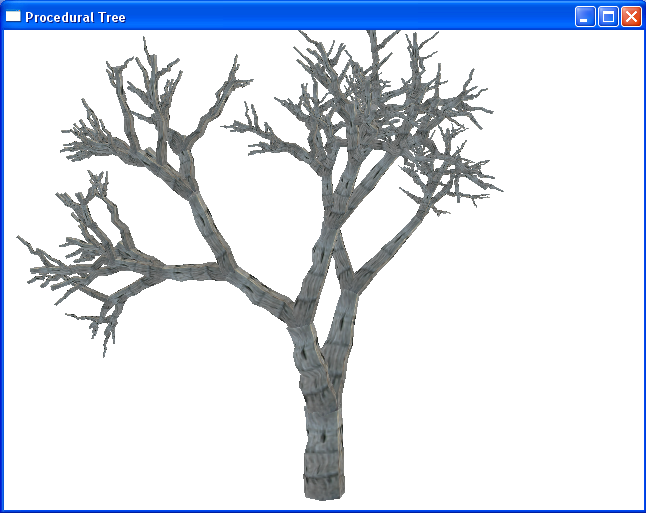

Tree Design Evolution

Basic Texture, No Branching

Basic Branching, Lighting

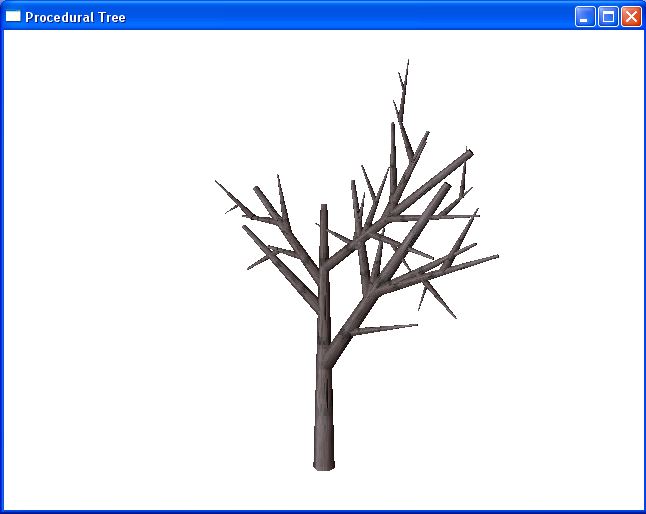

Model Leaves, Perspective

True Branching, Cherry Tree Properties

Gnarled Rotations, Proportional Trunk

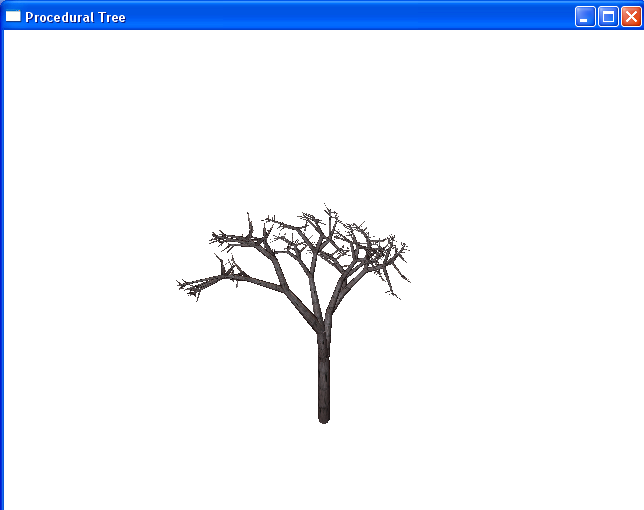

Smooth Gnarled, Reduce Leaf Noise

Increase Triangle Count, Decrease Sudden Knobs

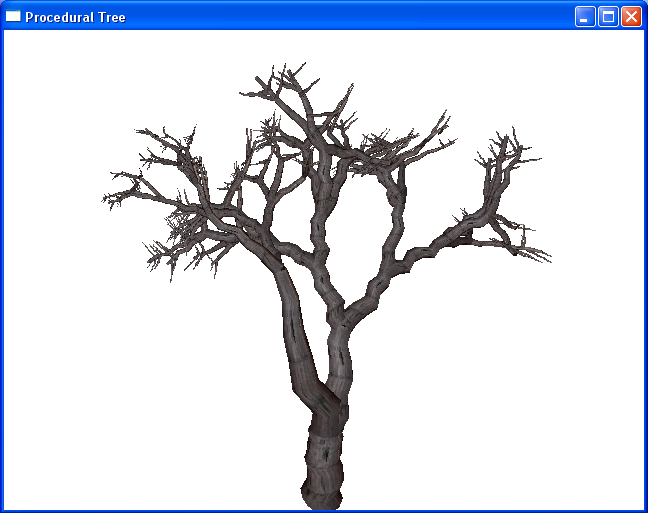

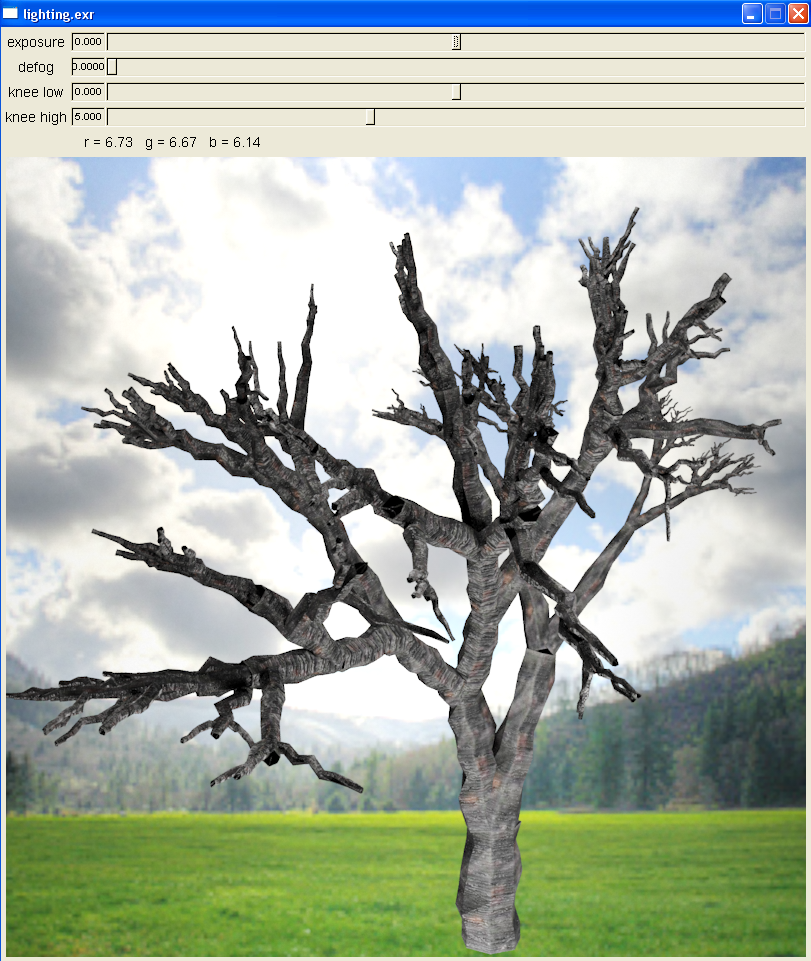

Natural Bark Perturbation With Displacement Mapping

First Render (no lighting, didn't pick a good tree model)

Second Render (slightly better lighting, backup, better model)

Third Render (backdrop, lighting)

Fourth Render (striped texture)

Fifth Render (correctly colored texture)

Sixth Render (enlarged, texture and bump mapping)

Seventh Render (fixed jaggy artifacts, basic lentical bark)

Eighth Render (displacement mapping for more realism)

Ninth Render (backdrop)

Ninth Render (different model)

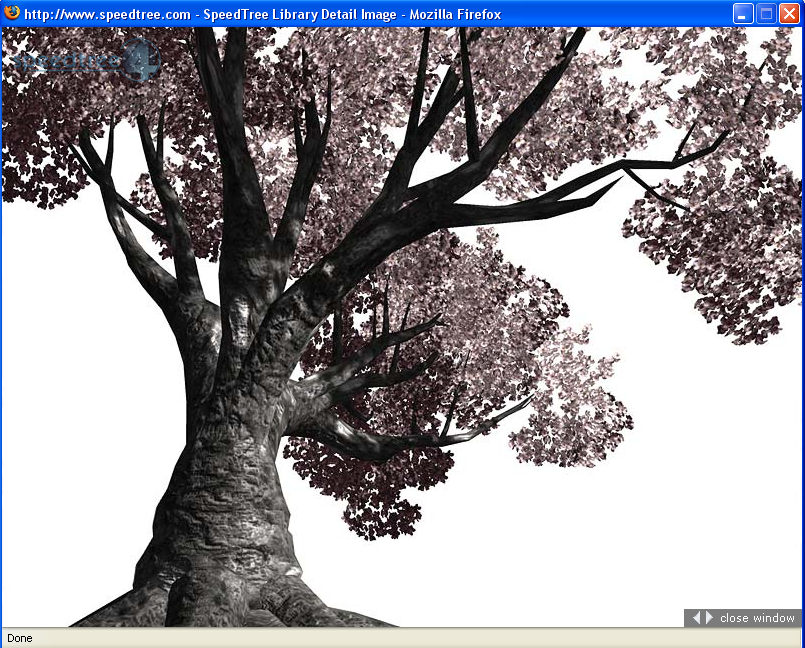

SpeedTree Implementation (for reference)

Procedural Bark (Tom)

Texture Generation

- Creating a bark texture as stated in [1] involves a complex series of equations dictating when and where fractures occur in bark given a particular length of a strip of bark. By combining these strips of bark and solving the fracture equations over a series of strips, we can combine these strips to generate a texture map. The fracture equations contain an innate variation law that allows for randomness in generation.

- After the fractures are generated, we overlay with a bump mapped bark texture to provide enhanced detail.

- However, the implementation in [1] works best for "fracture bark" trees whereas the cherry blossom tree has "lenticel bark" type. This means that we will need to extend the implementation in [1] from vertical fractures to horizontal fractures or will need to create procedural texture maps representing horizontal rather than vertical noise.

- The bark of a cherry blossom tree looks like:

Texture Mapping (Tom)

- After tree generation has concluded, we map coordinates from cylinders of branches directly onto texture coordinates of the procedural bark texture. With more time, we'd like to implement the mesh mapping strategy from [1] to ensure that fractures line up at branch junctions. However, given the scene complexity that we hope to achieve with blossom petals, such additional bark complexity may prove infeasible and not valuable.

Classic Plane Curves

Background

Prunus serrulata are dicots and possess five petals, five sepals, several stamen and a pistil.

We observed that in this case that the beauty of nature coincides with the beauty of mathematics. More specifically, the shape and geometry of these blossoms can be recreated with curves defined in polar coordinates.

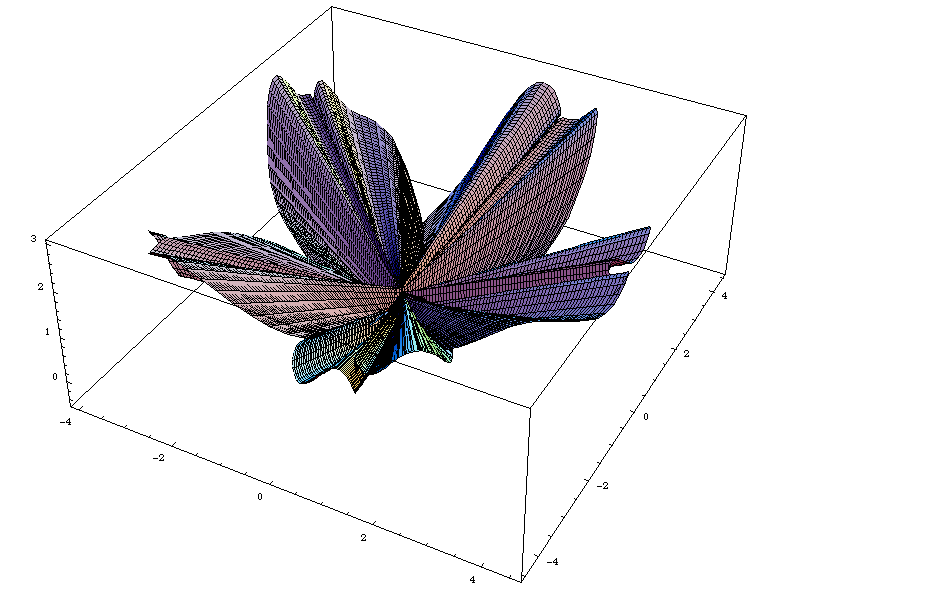

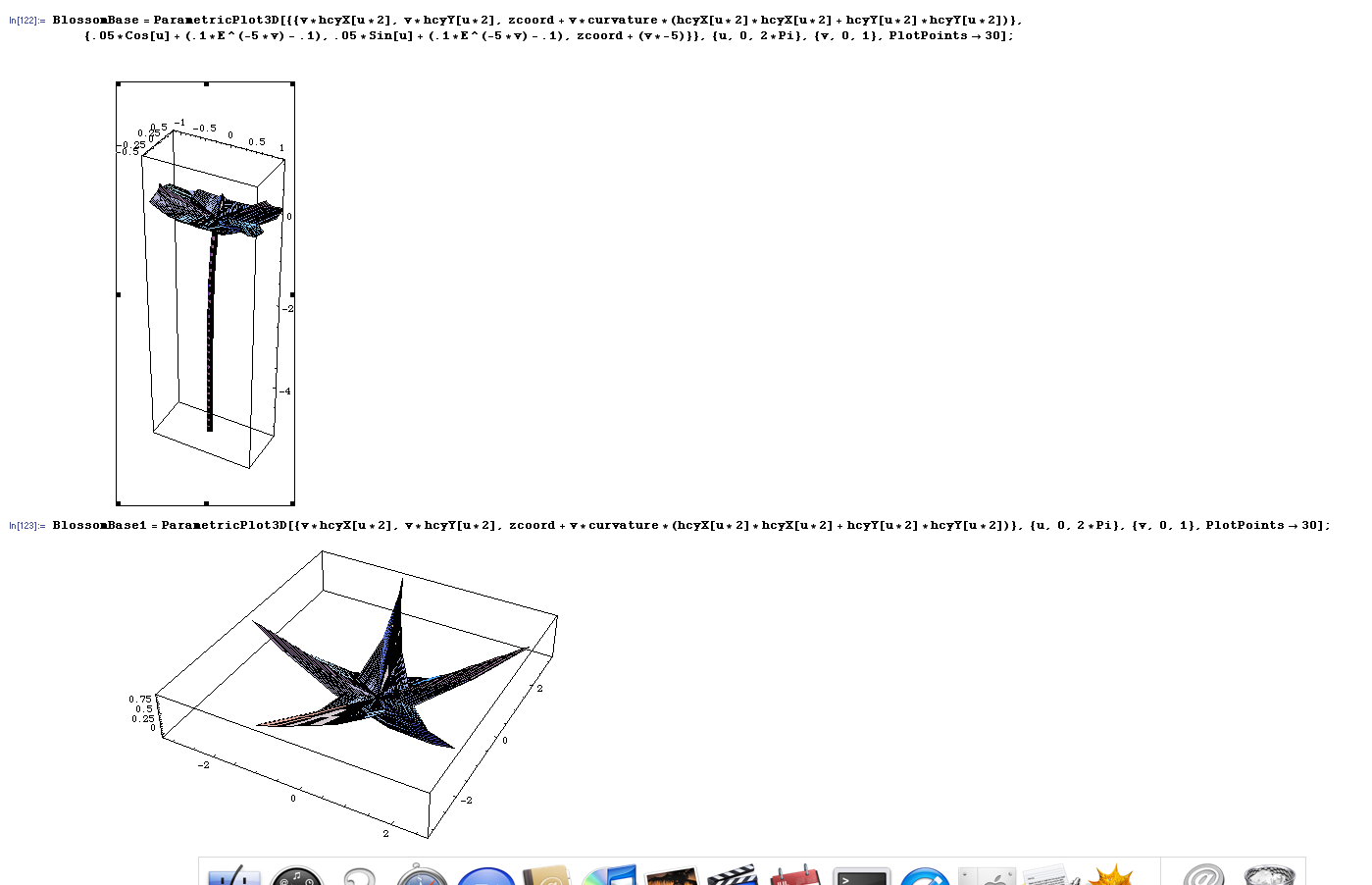

Blossom Rendering (Priscilla)

We chose curves that most closely resemble the shapes of most importantly the petals and sepals. The following is a diagram of the parts of a typical dicot:

The shapes of the petals resemble cardioids:

... and the placement of the petals are similar to the maxima of the 5 petal rose curve:

The star shape and positioning of the sepals resemble a 5 point hypercycloid:

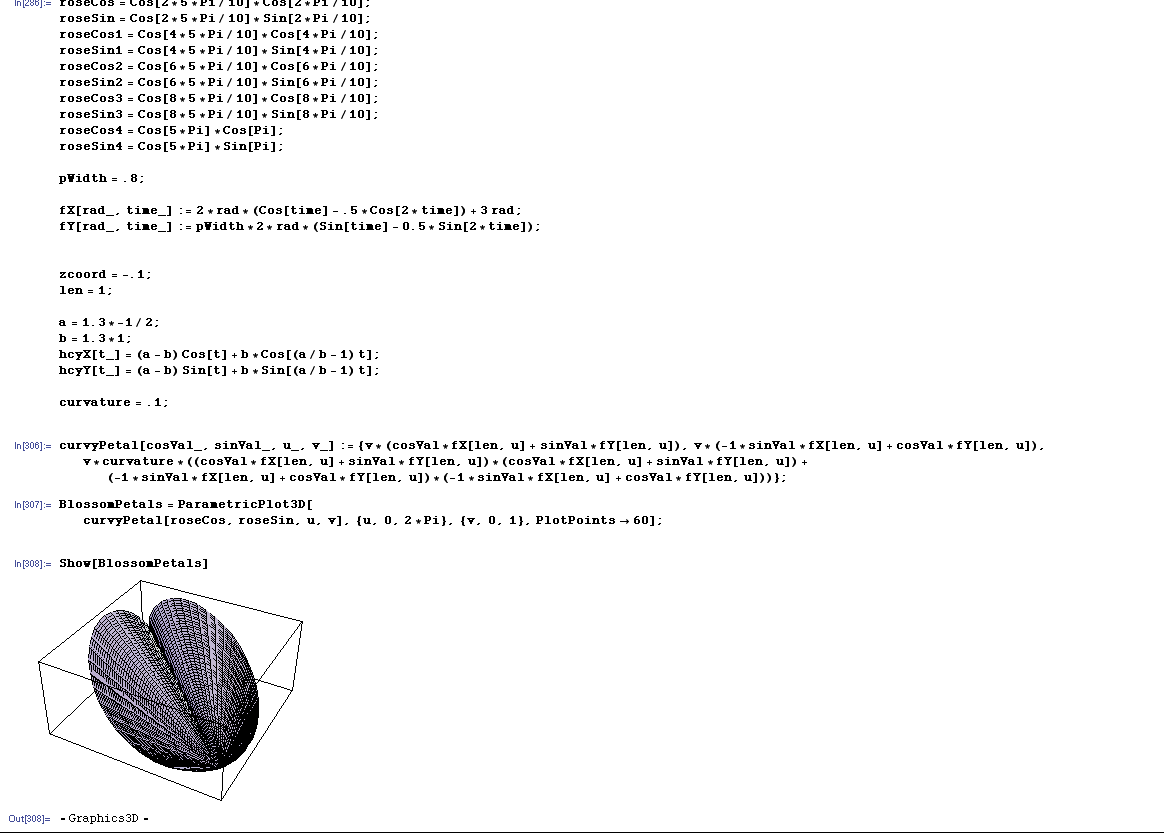

This is a mathematica modeling of a single petal, with the commands used:

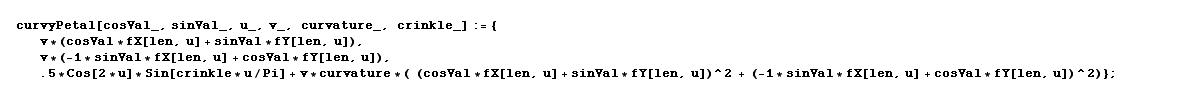

All petals together:

and then with varied sine and cosine noise added to the z-component as well as variance in curvature, so that the petals are not completely flat and emulate the imperfection in nature:

The petals are cardioids with the z-coordinate following the shape of a paraboloid to create the upcurving effect of the petals. The position of the petals around the center of the blossom are calculated according to those of the 5 petal rose curve.

The following is a Mathematica model of the sepals plus the stem:

The pistil and stamen are relatively straightforward to generate, as they are just segments with ellipsoids at the end.

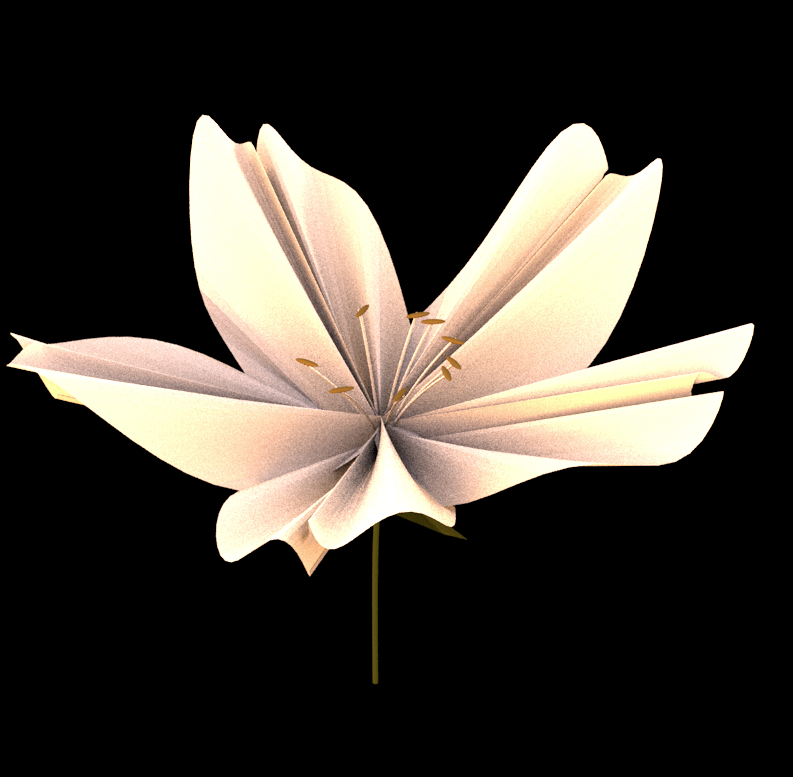

The following is a plain PBRT rendering of the final bare model:

Here is one of the images where I experimented with color, texture, and environment map infinite lighting. Notice also a rotated version where the sepals are displayed prominently:

Here is some experimentation with "dramatic" spot lights. lt gave a poor effect, as spot lights usually give a harsh appearance:

Texture Mapping (Priscilla)

After petal generation has concluded, we planned to generate randomized veins on the petal (all originating from the center) with a jitter transform and/or Worley cellular texturing (procedural). The vein pattern for the petals is actinodromous venation, in which three or more primary veins diverge radially from a single point. Primary veins support sequences of secondary (lateral) veins, which may branch further into higher-order veins. The secondary veins and their descendants may be free-ending, which produces an open, tree-like venation pattern, or they may connect (anastomose), forming loops characteristic of a closed pattern. Tertiary and higher-order veins usually link the secondaries, forming a ladder-like (percurrent) or netlike (reticulate) patterngrid size in every simulation step, which precludes continuous simulation of growth. Vein segments are straight, and segments double in length in each growth step, which yields artificial-looking long straight lines running through the pattern. [7] Due to time constraints, however, we were not able to devote time to this idea.

Subsurface Scattering (Priscilla)

Subsurface scattering (or SSS) is a mechanism of light transport in which light penetrates the surface of a translucent object, is scattered by interacting with the material, and exits the surface at a different point. The light will generally penetrate the surface and be reflected a number of times at irregular angles inside the material, before passing back out of the material at an angle other than the angle it would reflect at had it reflected directly off the surface. (Wikipedia)

Background

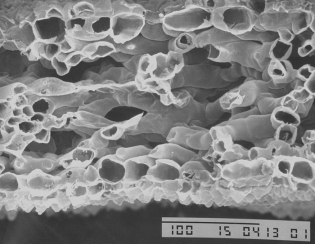

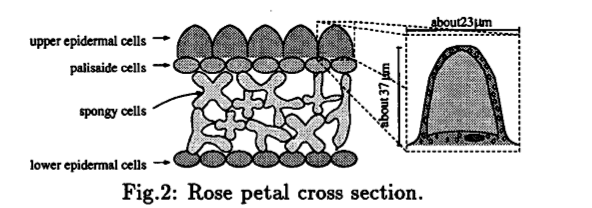

Rose petals are translucent and to achieve the realistic, silky, lifelike softness we must implement SSS. This may be achieved with the reflection model described in the paper by Hanrahan/Krueger. We will also study the structure and cellular layers of petals. So far, we have learned that two especially characteristic layers, such as upper epidermal cells which are dome-shaped and spongy cells which reflect much light, cause the unique appearance of rose petals.

[9]

[9]

- Petals resemble thin surfaces, and their cross-sections can be described by open contours. We hope to apply this and other plant biology knowledge to enhance the appearance of the sakura petals.

Petal SSS

I wrote a new petal material plugin to PBRT, which added the BxDF per Hanrahan and Krueger. I noted that in the diagram above of the cellular layers of petals was significantly less and thinner than the leaf diagram that the paper mentioned and took this as a justification of using the first order approximation for backscatter and the zeroth order approximation for the transmittance. I will calcuate the radiance by summing the radiance from surface and subsurface scattering, and the transmitted radiance from the sum of the radiance from absorption and subsurface scattering. From these values I calculate the BRDF and the BTDF and take into account the Fresnel coefficients. I used an index of refraction of 1.37 which is reasonable for epidermis of skin.

For setting the specular and diffuse values I used a color picker in The Gimp on the model image.

Final Single Sakura Blossom

One Blossom Next to Tree

Final Image