Research Overview

Physics-Based Sound Synthesis

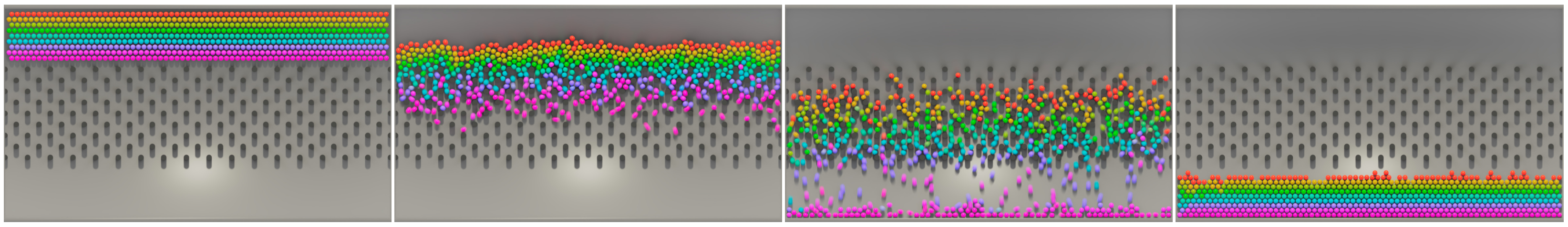

We are exploring how to synthesize synchronized and realistic sounds automatically for a wide spectrum of physically based simulation models (rigid bodies [JP06,WJ19], nonlinear thin-shells [CAJ09] and elastic rods [SJM17], liquid sounds using acoustic bubbles [ZJ09,L+16,X+23,X+24], fracturing solids [ZJ10,C+12], self-collision chattering [BJ10,ZJ11], combustion [CJ11], acceleration noise [C+12], cloth [A+12] & paper [S+16], etc.). One major focus has been developing efficient reduced-order algorithms to synthesize vibrations and sound radiation to enable realistic, real-time sound models for future virtual environments. We are excited to explore the frontiers of high-fidelity multiphysics sound rendering [W+18]. Recently, WaveBlender (with Kangrui Xue et al.) explores a new kind of GPU wavesolver that blends uniform-grid finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) discretizations and boundary conditions to achieve high-performance, low-noise sound synthesis for physics-based animations with rapidly moving, deforming, and vibrating interfaces.

Progressive Simulation

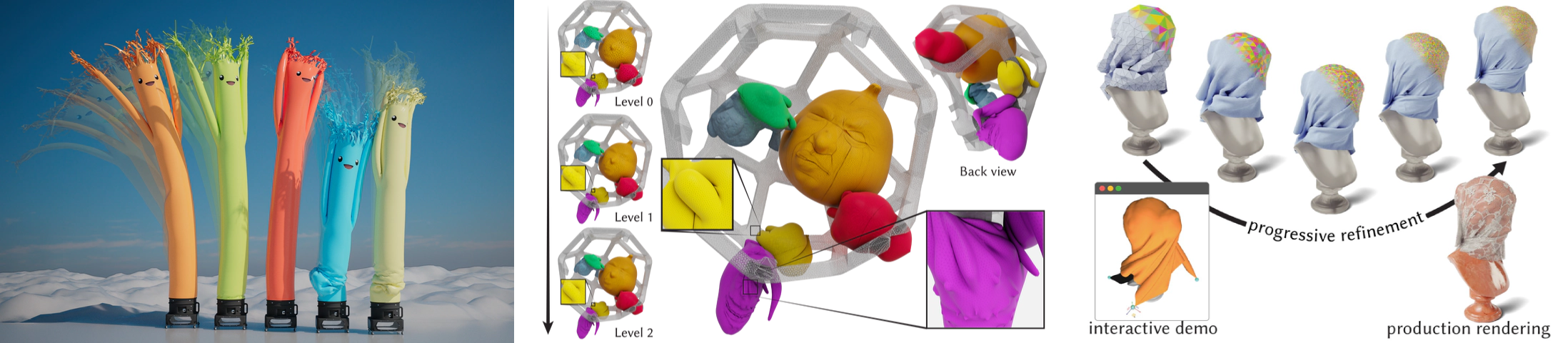

Progressive Simulation explores efficient, multi-scale model reduction methods for coarse-to-fine simulation of deformable solids, enabling high-quality physics-based animations with interactive coarse-scale previews that are faithful to their fine-scale progeny. This thesis work by Jiayi Eris Zhang explores quasistatic formulations for cloth [Z+22] and shells [Z+23], and generalizes to progressive dynamics [Z+24]. Collaboration with Danny Kaufman at Adobe Research.

NVIDIA Research

My work at NVIDIA explores new ways to use high-performance physics-based simulations for creative pursuits. For instance, ViCMA: Visual Control of Multibody Animations (with David Levin) explores a fun new take on multibody animation control where instead of using motion control to estimate plausible motions for objects with fixed appearances, we estimate plausible appearances for objects with fixed motions.

Deformation Processing

By and large, many of our contributions address efficient deformation processing methods: fast precomputed Green’s function models [JP99, PvdDJ+01, JP03], hardware-accelerated skinning [JP02, JT05], data-driven animation using motion graphs [JF03, JTCW07], dimensional model reduction and nonlinear reduced-order dynamics [BJ05, AKJ08, KJ09], deformable collision processing [JP04, KSJP08, BJ10], vibration-based sound synthesis [JBP06, BDT+08, CAJ09], fast lattice shape matching [RJ07], extra-warm yarn-level cloth [KJM08, KJM10, L+18, W+20], topology verification of loopy structures [QJ21], Phong Deformation [J20], etc.

Yarn-Level Cloth

Following the pioneering work of Terzopoulos and others more than three decades ago, computational models of cloth have been essentially “rubber sheets.” Starting with a sequence of works at Cornell with Steve Marschner and our students, we advanced fundamentally different computational cloth models based on direct simulation of constitutive yarns in pervasive contact. We devised a family of algorithms to efficiently simulate complex assemblies of inter-looping elastic rods and resolve millions of contacts [KJM08], along with space-time adaptive methods for exploiting temporal coherence in yarn-yarn contact computations [KJM10]. We invented Stitch Meshes to allow artists to interactively design realistic knitted garments with yarn-level details, while providing topological guarantees that the yarns will not unravel when simulated [YKJM12]. We continue to explore technology for faster and better simulation of yarn-level systems for the graphics and textile industries.

Numerical Methods for Reduced-order Models (ROMs)

Real-time and long-time simulation methods in computer graphics and sound have motivated the need for a variety of new reduced-order modeling techniques (dimension model reduction, low-dimensional subspace methods, etc.) that enable faster and cheaper simulations. We have long explored methods for reduced-order models (ROMs): precomputation-based schemes for data-driven ROM-based animation [JF03, JTCW07]; GPU-accelerated evaluation of deformable ROMs [JP02, JT05, BJ05]; dimensional model reduction methods for real-time subspace integration [BJ05]; cubature-based integration methods for subspace dynamics [AKJ08,CAJ09]; online model reduction (learning the basis and ROM “on the fly”) [KJ09]; ROM domain decomposition of nonlinear deformable models [KJ11] and efficient ROM-based simulation of fracture sound [ZJ10]; ROM-based multi-body contact solvers [KSJP08]; mode-adaptive, asynchronous integration of linear modal dynamics [ZJ11]; reduced-order collision processing via reduced-order bounding volume hierarchies [JP04], time-critical methods for hard real-time applications [KSJP08], and reduced-order self-collision processing [BJ10]; reduced-order water vibration and acoustic analysis [ZJ09,L+16]; and compression of ROM basis functions [L+14].

Pixar Research

My past work at Pixar (2015-2020) explored new ways of applying mathematics and physically based simulation to the Pixar creative process. For instance, I investigated analytical methods of mathematical physics to develop fast physics-based tools for artists, an example of which is our work on Regularized Kelvinlets for real-time deformable sculpting, and Dynamic Kelvinlets for elastic wave effects. After years of exploring numerical precomputation methods to solve equations ahead of time, it was interesting to revisit classical methods for “analytical precomputation.”

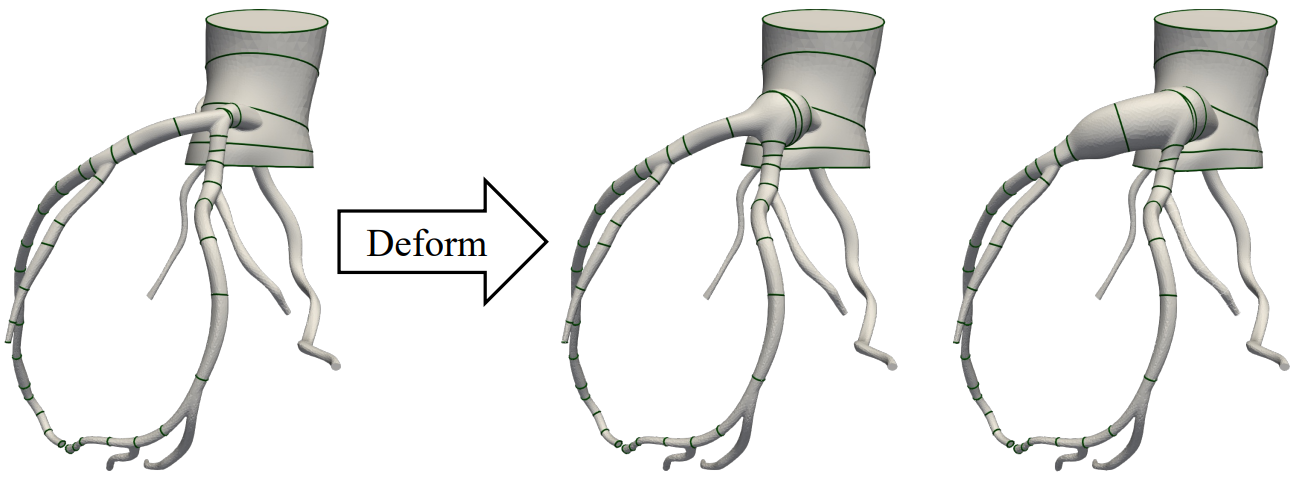

Cardiovascular Modeling

In collaboration with Prof. Alison Marsden, we have investigate methods for performing virtual-surgery-like deformations, and computationally explore the impact of vascular shape on patient hemodynamics using interactive geometry-editing of virtual patient-specific vascular anatomies [PP+23], and shape-editing using Regularized Kelvinlets [P+24].

We are exploring how to synthesize synchronized and realistic sounds automatically for a wide spectrum of physically based simulation models (rigid bodies [JP06,WJ19], nonlinear thin-shells [CAJ09] and elastic rods [SJM17], liquid sounds using acoustic bubbles [ZJ09,L+16,X+23,X+24], fracturing solids [ZJ10,C+12], self-collision chattering [BJ10,ZJ11], combustion [CJ11], acceleration noise [C+12], cloth [A+12] & paper [S+16], etc.). One major focus has been developing efficient reduced-order algorithms to synthesize vibrations and sound radiation to enable realistic, real-time sound models for future virtual environments. We are excited to explore the frontiers of high-fidelity multiphysics sound rendering [W+18]. Recently, WaveBlender (with Kangrui Xue et al.) explores a new kind of GPU wavesolver that blends uniform-grid finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) discretizations and boundary conditions to achieve high-performance, low-noise sound synthesis for physics-based animations with rapidly moving, deforming, and vibrating interfaces.

Progressive Simulation explores efficient, multi-scale model reduction methods for coarse-to-fine simulation of deformable solids, enabling high-quality physics-based animations with interactive coarse-scale previews that are faithful to their fine-scale progeny. This thesis work by Jiayi Eris Zhang explores quasistatic formulations for cloth [Z+22] and shells [Z+23], and generalizes to progressive dynamics [Z+24]. Collaboration with Danny Kaufman at Adobe Research.

My work at NVIDIA explores new ways to use high-performance physics-based simulations for creative pursuits. For instance, ViCMA: Visual Control of Multibody Animations (with David Levin) explores a fun new take on multibody animation control where instead of using motion control to estimate plausible motions for objects with fixed appearances, we estimate plausible appearances for objects with fixed motions.

By and large, many of our contributions address efficient deformation processing methods: fast precomputed Green’s function models [JP99, PvdDJ+01, JP03], hardware-accelerated skinning [JP02, JT05], data-driven animation using motion graphs [JF03, JTCW07], dimensional model reduction and nonlinear reduced-order dynamics [BJ05, AKJ08, KJ09], deformable collision processing [JP04, KSJP08, BJ10], vibration-based sound synthesis [JBP06, BDT+08, CAJ09], fast lattice shape matching [RJ07], extra-warm yarn-level cloth [KJM08, KJM10, L+18, W+20], topology verification of loopy structures [QJ21], Phong Deformation [J20], etc.

Following the pioneering work of Terzopoulos and others more than three decades ago, computational models of cloth have been essentially “rubber sheets.” Starting with a sequence of works at Cornell with Steve Marschner and our students, we advanced fundamentally different computational cloth models based on direct simulation of constitutive yarns in pervasive contact. We devised a family of algorithms to efficiently simulate complex assemblies of inter-looping elastic rods and resolve millions of contacts [KJM08], along with space-time adaptive methods for exploiting temporal coherence in yarn-yarn contact computations [KJM10]. We invented Stitch Meshes to allow artists to interactively design realistic knitted garments with yarn-level details, while providing topological guarantees that the yarns will not unravel when simulated [YKJM12]. We continue to explore technology for faster and better simulation of yarn-level systems for the graphics and textile industries.

Real-time and long-time simulation methods in computer graphics and sound have motivated the need for a variety of new reduced-order modeling techniques (dimension model reduction, low-dimensional subspace methods, etc.) that enable faster and cheaper simulations. We have long explored methods for reduced-order models (ROMs): precomputation-based schemes for data-driven ROM-based animation [JF03, JTCW07]; GPU-accelerated evaluation of deformable ROMs [JP02, JT05, BJ05]; dimensional model reduction methods for real-time subspace integration [BJ05]; cubature-based integration methods for subspace dynamics [AKJ08,CAJ09]; online model reduction (learning the basis and ROM “on the fly”) [KJ09]; ROM domain decomposition of nonlinear deformable models [KJ11] and efficient ROM-based simulation of fracture sound [ZJ10]; ROM-based multi-body contact solvers [KSJP08]; mode-adaptive, asynchronous integration of linear modal dynamics [ZJ11]; reduced-order collision processing via reduced-order bounding volume hierarchies [JP04], time-critical methods for hard real-time applications [KSJP08], and reduced-order self-collision processing [BJ10]; reduced-order water vibration and acoustic analysis [ZJ09,L+16]; and compression of ROM basis functions [L+14].

My past work at Pixar (2015-2020) explored new ways of applying mathematics and physically based simulation to the Pixar creative process. For instance, I investigated analytical methods of mathematical physics to develop fast physics-based tools for artists, an example of which is our work on Regularized Kelvinlets for real-time deformable sculpting, and Dynamic Kelvinlets for elastic wave effects. After years of exploring numerical precomputation methods to solve equations ahead of time, it was interesting to revisit classical methods for “analytical precomputation.”

In collaboration with Prof. Alison Marsden, we have investigate methods for performing virtual-surgery-like deformations, and computationally explore the impact of vascular shape on patient hemodynamics using interactive geometry-editing of virtual patient-specific vascular anatomies [PP+23], and shape-editing using Regularized Kelvinlets [P+24].